The Ever-Present Reality of Good Friday

Silence and suffering are two things that make humans feel uncomfortable. Good Friday teaches us that silence can be beautiful, and suffering need not feel meaningless.

This post is not about singing, or voice teaching, or classical music.

That’s partly because most of my creative bandwidth this week is dedicated to singing at Holy Week services, which, as is the case every year, have me in a reflective, pensive mood.

It’s also because this is my Substack and I can write about whatever I want, so there. ;)

Instead of music, today I want to write on another subject that’s near and dear to my heart: Catholic liturgy.

I am no liturgical expert, but I’m married to someone with three theology degrees who wrote an entire Master’s thesis dedicated to the post-Vatican II reform of the Roman liturgy. I’ve also done plenty of my own reading and learning over the years, not to mention been a member of several parishes with pastors who cared about doing liturgy well. I wouldn’t call myself a liturgy nerd, per se, but it’s a topic I enjoy discussing, and, given my background, it’s probably safe to say that I know more about it than your average American Catholic.

Holy Week is an intense time for Christians. It’s a time for us to contemplate the central mysteries and truths of our faith, and for those who choose to enter fully into these mysteries, it can be quite the emotional investment. (And for the singers who provide music at these services, it’s quite the vocal investment, too.)

All of the Holy Weekly liturgies, from Palm Sunday to the Paschal Vigil on Holy Saturday, are incredibly beautiful, rich, and meaningful, and it’s hard to choose a favorite. I think I change my mind every year, as the various elements of each service speak to me in a new way each time.

But Good Friday stands out as different from the others, in a way that I think is important for us, as Christians, to acknowledge.

One of my favorite parts of the Good Friday liturgy is the silence.

The procession happens in silence. Normally, the procession is accompanied by music, but on this solemn occasion, there is no sound of any kind.

When the altar party reaches the sanctuary, the clergy prostrate themselves, lying facedown on the floor. The rest of the congregation falls to their knees.

Given what we are commemorating in this liturgy, this feels like the only appropriate thing to do.

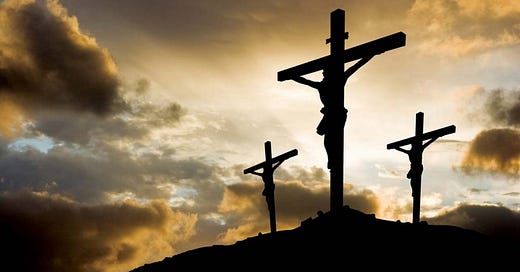

The silence in those opening moments of the Good Friday service, and the penitential liturgical postures that we assume during that time, impels each of us to contemplate deeply what we are commemorating: Jesus, true God and true man, died willingly on the Cross out of love for each and every one of us, to save us from our sins, so that we can have eternal life with him, instead of the eternal punishment we actually deserve as sinful, fallen human beings.

In that silence, we can feel a lot of things. We can feel gratitude, wonder, love, and devotion; but we may also feel sorrow, guilt, shame, and remorse for our sins – the very sins that Jesus died for.

This is the thing about silence: it often forces us not only to feel, but to self-examine and arrive at honest, if uncomfortable, conclusions about ourselves and who we are before such an all-powerful, all-merciful God.

And when that happens, we often seek to fill silence with noise, activity, or anything that will distract us from what we are experiencing inwardly.

During the silence of Good Friday, there is nothing to distract you. There is not even much to look at: the altar has been stripped of its usual seasonal linens and other sacred items, which were removed after the Blessed Sacrament was laid in repose elsewhere in the church the night before. Everything is bare. The tabernacle is open and empty. The church’s statues and images are all shrouded in purple cloth, hidden from view. The normal things we rely on to help stimulate our religious imagination or enhance our devotion during worship are gone.

It is just you and the silence.

I grew up in the 90s and early 2000s, when, often, very little silence was to be found during liturgy. There was constant sound, constant motion, constant doing.

A couple years after we were married, my husband and I started attending the Latin Mass. The contrast between the silence and reverence of this liturgy, and the lack of stillness that had pervaded the liturgies I’d experienced growing up, was striking.

Because certain parts of the Latin Mass are said silently by the priest – particularly the Canon, or Eucharistic prayer, during which there is no music or other activity happening concurrently – I found myself actually able to pray. The absence of noise allowed me to follow along in my missal with what was happening, and participate interiorly, making the words of the liturgy my own.

The Latin Mass is, unfortunately, often very polarizing amongst Catholics. There are many who love it and prefer it to the Novus Ordo; and there are those who eschew it entirely because they believe it is obsolete and impenetrable. In conversations with folks who are fans of the constant-sound, constant-motion ethos of the “contemporary” 90s liturgies I grew up with, there is almost a sense in which they seem to be threatened by something as old and traditional as the Latin Mass.

It’s hard to imagine feeling threatened by something so beautiful and reverent that’s been around for literal centuries. I’m not entirely sure where that sentiment comes from, but my theory is that it has to do with the uncomfortableness of silence that impels one to be still and pray.

If your experience of liturgy is constant noise, sound, motion, external stimulation, doing, then a liturgy full of silence, where your choices pretty much boil down to engaging interiorly or completely disengaging unto boredom, is probably going to feel very strange and uncomfortable.

Modern liturgists will say, “But the word ‘liturgy’ means ‘the work of the people!’ People should be able to participate in the liturgy by having some kind of active role!”

Traditional liturgists would say that, yes, roles are important, and there are many roles in the liturgy that need to be filled; but what is more important than doing something is the interior participation of each congregant present. That is what we mean when we say liturgy is “the work of the people.”

The work of the people is to participate in God’s work – that is, Jesus’ saving work on the Cross. God is the main actor here, not us.

On Good Friday, we commemorate, in a unique way, Jesus’s sacrifice on the Cross at Calvary.

But we would do well to remember that every Mass is a re-presentation of the sacrifice at Calvary.

And it is in our participation in this sacrifice that we can unite our prayers and sufferings to Jesus’ saving work.

Given this, it should seem natural to invite silence at Mass. Good Friday may be the most somber day of the liturgical year, but for Catholics, it’s also an ever-present reality.

Good Friday pervades every Mass. We are people of the Resurrection, yes; but we cannot celebrate the Resurrection without first recognizing what came before it.

Catholics believe that one’s suffering, when united to Christ’s suffering on the Cross, is salvific – meaning that it has saving merits – both for ourselves and others.

This is an incredible gift. Jesus has sanctified suffering, and enables us to unite ours to his in a way that allows us to participate in his saving work. It is a special way in which we can offer prayer and sacrifice, both for ourselves and others.

This kind of prayer and sacrifice is not found in doing. It is not found in motion. It is not found in distraction. It is found in the stillness that comes as a by-product of interior participation in the liturgy, and the humility we experience as we kneel before Our Lord, in silence, at Calvary.

None of us is promised a life without suffering. But because of what happened on Good Friday, suffering does not have to be meaningless.

It might sound odd to hear a musician say that her favorite part of the Good Friday liturgy is the silence. After all, as church musicians, we’re there to provide an auditory experience meant to help enhance one’s worship.

And, of course, I love doing this, too. The music of the Church, throughout all eras, is something very important to me, and being able to provide music at Mass is, in my opinion, a great privilege.

But I think there is a time for sound, and a time for silence.

The next time you encounter silence that feels uncomfortable, and you find yourself casting about for something to say or do to fill it, consider embracing it instead. Rather than avoiding it, or avoiding what comes up interiorly as a result, remember that it is in silence where we can find a deeper connection to ourselves and to God.

And that deeper connection allows us not only to serve God more fervently and work in His vineyard in whatever way He has called us to do so, but can also increase our joy.

So you can bet that, after the marathon that is Triduum (especially if you are a church musician), I will be celebrating on Easter Sunday like there’s no tomorrow. (After I figuratively peel myself up off the floor, that is.)

But first, I will embrace the silence of Good Friday.

I ADORE this. I came from a Protestant Evangelical background and as an adult, I have found such BEAUTY in liturgical Christianity, and now find myself drawn to Anglo-Catholicism. The expression of ORDER, of the BEAUTY of liturgy - has added an immense value to my life. To want to know more and learn more - this is my first Easter in this tradition and I love that the Daily Office begins to remove the Gloria Patri, then the Hymns, then the Canticles - everything becomes bare bones - and you are left with the just the core - no filigree. What a beautiful post, and thank you for writing it.

Your comment about people feeling threatened by the traditional mass is really interesting. I think in many ways, things with long historical traditions make people feel irrelevant and small. it requires humility to accept your oneness with something that’s so much larger than yourself.